Bouncing down the road in a red extended cab truck with five people all in the front, my mind began to wonder if we would ever get to this unknown place. With each new pothole I felt a new pain in my body—a bruised behind, a new knot in my back, another stiffness in my scrunched up legs. Rather droopy from the Dramamine I took to prevent the barfing sensation I so often get when riding vehicles in Indonesia, my head would fall down to my chest, only to awaken to an upright position 5 seconds later from yet another deep bump of a new pothole. While imagining this scene, your mind may conjure images of Iowa gravel road potholes, but Iowa potholes are pavement in comparison to this road’s potholes—the only road available for this 6-hour journey to the Sarmi kampung, Imanuel Podena.

If this journey were all paved roads, it may take 3 hours. If this journey was on all Iowa gravel roads, I think it may take 4, maybe 4 ½ hours. But with these Papuan roads it takes 6 hours; 8 if you go all the way to the city of Sarmi. It’s not just the road’s surface that makes the journey so slow. Mountains, lakes, rivers and jungle exist where this 1.5-lane road must travel, therefore you’re greeted by constant turns—curves so tight that one must honk their horn before going around each corner to warn off vehicles who may come from the other side. The road switches between gravel, mud, asphalt, and wooden bridges with giant nails and missing boards. Holding my breath while crossing these overpasses became a common game as I thought for sure we would fall through the openings—“We survived that last one, but this one is just gaping open. Surely we will fall through this time.” Holding my breath didn’t prevent the fall, but at least it prepared me for it.

Yet nothing prepared me for the kampung (village). I had no pre-conceived notions of where I was going; perhaps someone told me something, but due to my limited language skills and my new habit to tune out a lot of what people say to me, I came with an open mind and a limited knowledge of what I was getting myself into. I knew it was in the jungle, and I knew it was near the ocean (I had looked it up on a Papuan map before leaving). Many also warned about copious amounts of mosquitoes. They were right.

No one warned me that there wouldn’t be some sort of outhouse—instead the jungle and ocean provide a place of relief. No one warned me that I would be eating a copious amount of manggas for lunch, and by that I mean only mangos. They also didn’t tell me that my face would have some weird allergic reaction to the mango’s skin. I had no previous explanation that broken floor boards would be my stiff resting place at night, electricity would most likely be unavailable, drinking water would be difficult to come by, or grasshoppers as big as my hand would be my new nighttime best friends. Also, no one explained to me that this kampung would become my haven, my breath of fresh-air, my pick-me up, my jump-start back to life—the reason I’m here in Indonesia. No one told me I would leave my heart there and yearn to go back to retrieve it. But I suppose no one, not even I, could have guessed that one.

Sand provides the ground for this prime rental beach location composed of village houses, or basically wooden boxes held high on stilts, usually with one or two rooms sparsely decorated. Most people have a kitchen outside, with a fire-pit stove and perhaps a wooden wall handy for storing pots and pans. Some just put nails into the sides of their house and hang the pans, almost like people nail window flower boxes to houses in the U.S. A few people have built a second, much smaller box-like structure in the back of their piece of beach, with a sheet over the door. This serves as a kamar mandi, or shower room. Others just use the fresh water stream for showering, or in the case of the children, just dive straight into the encompassing ocean for a quick, salty refresher. This is one of the beach kapung(s).

Two kilometers up a very narrow road, which looks more like a U.S. country house’s lane, is another village. Essentially the same village but built more inland—same families, same people, and same idea. In fact, many people I met at the beach kampung also have a house in this inland kampung (something I’m trying to understand). These houses are more “house” like (as westerners know houses to be), with 4 stonewalls and a roof. Yet they’re still only 1 or 2 rooms, and have kitchens outdoors and no running water. Most have a squat toilet though and electricity until at least 11 PM. One still sleeps on the floor. This village is where we ended up staying, after the first day, due to the fact that we were basically starving on the beach with no food and nowhere to make it. I’ll admit I was a bit happy about this—mainly because of the toilet (I had diarrhea due to bacteria in my system for at least 2 weeks now and was not enjoying the whole going outdoors thing), and because of the lights. When the sun sets at 6:00 PM, not having electricity is actually more challenging than you would think.

I was invited along on this village trip with the educational training department at P3W. I do not work directly with this department, so basically my purpose was solely to observe another part of Papua. The two women accompanying from this department gave informal education classes to the women of the village—one on baking and one on flower arranging. Due to living in such an isolated area, most people just eat fish and a gooey substance called Papeda every meal, everyday. So baking classes may not seem like a big deal, but being taught how to make banana cake for the first time, or even a chocolate cake for that matter, is rather exciting and worth something, especially to those taste buds these delicious morsels have never tantalized before.

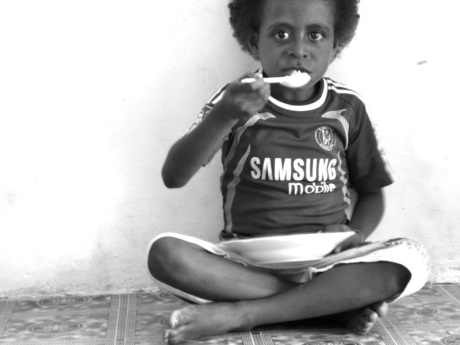

Sitting on the sidelines, I did the thing I do best—made friends. I started with the children. They’re the easiest targets. Most have never seen a white person before, at least not in full living and breathing form. Completely enamored with this strange white person, they sit at least 20 feet from me in clusters of 10 or 20 children. Yet they’re extremely shy and when spoken to either erupt in giggles or run a few feet away. Eventually, after the children had observed me for at least 30 minutes, I decided to approach them to understand what game they were playing the dirt. It happened to be marbles, so I asked a few to show me how play. Either they didn’t understand my broken bahasa, or they were just too shy to actually tell me how to play marbles. But, through show-n-tell, I learned the game while squatting on the ground, flicking marbles back and forth. A half hour later when my knees couldn’t take it anymore and the sun had caused all surfaces of my clothes to stick to my skin, I asked if we could sit under a tree.

From that point on, they were my new best friends. We had all sorts of fun—playing invented games in the ocean, bathing in the river, picking beans in a field, eating, laughing, and holding hands. Three girls in particular were my absolute favorite. They were in the original group I had approached to play marbles, and one of them had been the main teacher in that scenario. After that, they seemed to think they were my mentors, or perhaps the other way around… I’m not so sure. But in any case, they never left me, and enjoyed pointing out my blue veins, white teeth, or straight hair.

Through pinang I also became friends with some of the women of the village. During the first cooking class I sat amongst a few of the village women. One woman, who I later found out was Ibu Yosmina, immediately began talking to me—“Siapa nama? Dari mana?” (what’s your name, where are you from?) I think maybe the third question was, “Sudah makan pinang?” (Have you already eaten pinang?) She was rather appalled by my answer of “no” and insisted that I later try. When the women were split into cooking groups, Ibu Yosmina and a few others shouted out that I was going to be one of their group members, too, much to the amusement of the P3W women. So, off I went with Yosmina and a few others to make a delicious banana cake. Waiting for the cake to bake turned into an opportune time to chat about many things, including teaching me how to eat pinang.

Pinang, also known as beetle nut, is something that is native to Papua. It’s completely embedded into the culture here, and almost every does it, including 7-year-old children in the villages. It’s essentially a low-stimulant drug. If you want more information on this nut, you can find a Wikipedia entry here.

Ibu Yosmina (along with at least 30 villagers observing) became my pinang guru. You take the pinang nut, which is white-ish in color, and put it in your mouth and kind of chew on it with your molars. Some people peel it; some just chew it with the outer shell on it. You then have some another plant (Sirih) that is kind of like a green stick. And then you have kabur, which is ground up white chalk. You dip the sirih into the kabur, and then bite it off and chew it along with the pinang, which stays in your mouth. Somehow the mixture of sirih and chalk make your spit this extreme bright red color. You then have to spit out this liquid that is formed in your mouth. When I first got to Papua I thought there were blood splatters all over the ground, but it’s just the pinang spit of thousands of Papuans.

When I tried it I didn’t feel anything except a numb mouth. Apparently if you chew enough of it though it numbs your whole body. And then if you chew too much, you get really dizzy and you have to lie down. It’s kind of like a coffee stimulant. This stuff actually looks quite disgusting. And I guess the concept is kind of gross, too, if you’re not familiar with it.

Forming this relationship with Yosmina was very important to me, especially because it gave me ideas about returning to this village to produce a podcast on women in Indonesia. Since I’ve already spent some time in this village, it would be great to go back there for interviews since relationships are already budding and trust wouldn’t be as big of an issue. I think if I asked Yosmina if I could join her for the day, she would have no qualms with it. Therefore, if I can talk P3W into taking me back I would like to spend 4 days learning about the women of this village.

The first day would be visiting and chatting, re-uniting relationships and explaining what I want to do, asking the women if they’d be wiling to meet me the next day and talk with me about their lives. I would hope the next day could incorporate a gathering of women talking about an array of topics about life in this beach/jungle village. I particularly want to talk to them about their meaning of life—being in such an isolated area, knowing nothing other than having children and providing for them, I really want to know what they live for. I’m not meaning that in a condescending way. It’s just such a different life than what I know. I live for wanting to improve the world that I live in—making a difference on society. So what do they live for? What is their meaning of life? Perhaps the same thing: making a difference on their own society, their own children, improving the village they live in. Who knows—but that’s why I want to ask. The third day I would hope to follow Ibu Yosmina, or another woman in the village, for the entire day. Focus on one woman’s story—see what she does from sun up to sun down, get more personal stories about her life in the village. The last day would be for any last-minute interviews, hanging out with the kids, and more discussion with the women.

This is only the dream of an informal plan, but I do hope I can go back to this village and form deeper relationships with these women and children. Like I said, I left my heart in this village—I fell in love with their way of life, their charismatic personalities, their jungle and ocean. I want to understand their daily hardships. I want to understand this kind of rural, isolated living. I want to be a part of who they are in the scheme of this larger world.

This trip brought the life back into me. It reminded me why I’m in Indonesia, why I wanted to come in the first place, what my “purpose” is here, what I want to do here, what I want to get out of being here. It also gave me a pleasant reminder to the kind of person I am, my passion, my gifts, and how I can use those gifts for the greater cause of this world.

______________________________________________

I was going to attempt to post photos into my writing, all clever-like so they synchronized with what I wrote. But in the end that just seemed like too much work, and way too much time that I don’t have. Therefore, you’re getting them all lumped together here at the end.

Some of you may know about my VERY disappointing news that my Nikon SRL camera had some malfunctioning issues and is now back in the U.S., California to be exact, getting doctored at the Nikon repair shop. I was so, so very sad about letting that camera go. But, on the plus side, I came to realize that point-and-shoots really CAN take good photographs. So, they may not be as good of quality as they could be… but they do the trick.

wow, I really want to visit. Looks like you had a memorable time!

Rae: Great to get this new edition of your blog; and so pleased that you are feeling back on track. And good to know how inspired you are to go back – that’s very cool. It’s been good talking to you these last couple of days. Hope you’re feeling better.